A.C.T.I.O.N.

What is A.C.T.I.O.N.?

A.C.T.I.O.N., otherwise known as A Cautionary Torment Imposed On the Nameless is the first in a series of genre-oriented

games that are to display a range of iterated concepts in short periods of time, resembling a professional design environment. It is a 2D

game based on exploration and resource management.

Scope and limitations

Following the premise of its series, the development project lasted one month, starting from January 18th, and finishing on February 19th. Everything about it was done by me, with the only exception of the two songs used as music, and for the following external code:

- Freetype

- GLEW

- OpenGL

- PhysFS

- SDL2

- SDL2_Image

- SDL2_Mixer

- Tiled

A.C.T.I.O.N. index

- Development process

- First iteration

- Second iteration

- Third iteration

- Playtest feedback

- Project closure

- Conclusions

- Release link

Development process

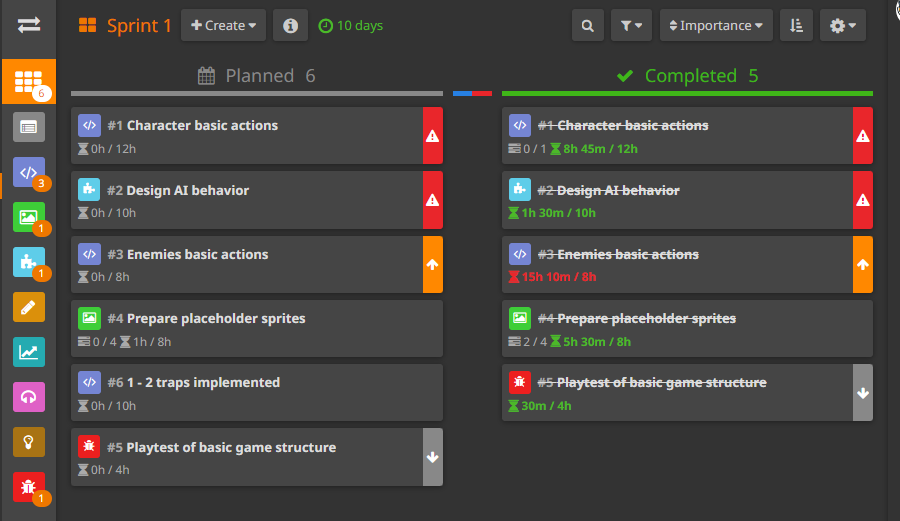

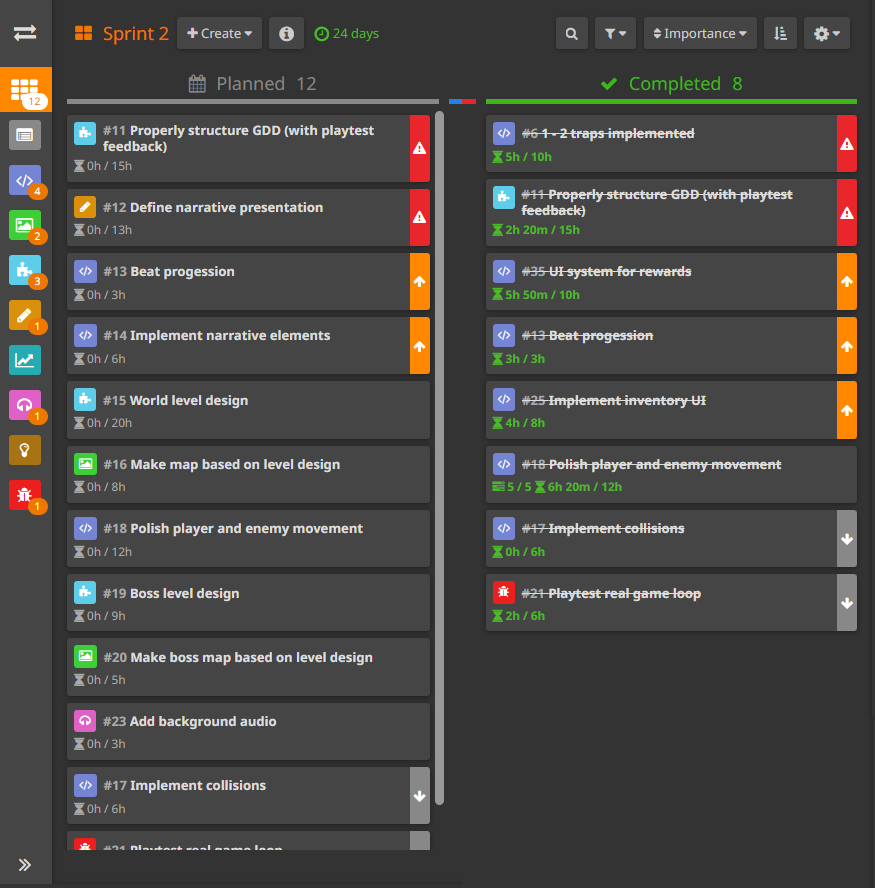

The development process followed an agile methodology, iterating the game thrice in a month. The distribution of tasks was done in HacknPlan, defining from day 1 everything that had to be done,

and how much time we expected to need. Once a sprint began, we revised all its tasks, considering whether we missed something, and if all priorities had to be kept the same, and then began the stablished

roadmap until the sprint ended or it had to be adapted due to unforseen circumstances.

First iteration

The game was conceived from an iconic idea: a child abandoned into the wilderness as an offering. The experience in mind was a slow-burn of surviving in a highly hostile environment, being the bottom of the food

chain, and learning to survive nonetheless, emotionally punctuated by moments of chaos when the player makes a mistake, and the looming threats around them begin chasing. However, because the demos are simple

and short experiences, we recognized we wouldn't have enough content to offer a rewarding progression that compensated the constant high tension the experience needed to remain faithful to itself.

As such, the core of "surviving against hostile nature" and "being powerless" remained, but the gameplay's feel defaulted to something more standard to accomodate the development scope. During this initial identity-searching

period emerged many ideas, which were noted and ordered based on what elements of the game it related to, and how implementation-friendly they were. With a solid basis around which we could more or less close the design core,

we established the game pillars, and began defining the GDD we used during the first iteration.

By the end of this sprint we had the basic skeleton of the gameplay, along with placeholders sprites (that sadly ended up making it into the final release). However, since the experience wasn't implemented yet, the playtesting

we did was purely done by the development team (me), to ensure the quality and consistency of movement, more than to judge whether the feel was adequate to what we wanted to convey.

Second iteration

This sprint was greatly defined by two things: a very clear definition of what the final gameplay would be like, and incidents. In terms of documentation, as always, I will attach

the GDD corresponding to this point of the project. The rest of this section, then, will be dedicated to the aforementioned incidents; it might sound like whining, because it is, but it has also been a key part of the development

process, so I'll be transparent about this too. TL;DR: I spent time (unefficiently) that I could have used to do (better organize) playtesting.

The first incident was a job offer for which requested I did some level design practices in Unity; since the purpose of this genre-oriented series is precisely a showcase of my professional skills to appeal to members of the industry, it was a

no brainer to drop what I was doing, and take my chance at entering the workplace. That took two entire days, which might not sound like much, but is 15% of the sprint's duration.

The second incident occurred by the end of the sprint, during the organization of the playtesting. I knew that, because of the game's nature, I needed to conduct each person's testing ensuring that the other testers didn't get

second-hand experience that could condition their playstyle. Because of that, and for the convenience of my testers, I appointed a series of hours, spread among different days. Disaster stroke when I called the first tester, sent

them the file, executed it... and it crashed. Because of course it did. On my computer it worked perfectly fine, but not on theirs. Of course, I had already tried my release file in other computers, but didn't have any problem

on those. At that moment, with only the two of us, I didn't have many hints on what was going on, and not wanting to force any of the other players to contact me outside the apppointed time, I ended up needing a couple of days to

ensure that the crash was recurrent for everyone else, and to solve it. Which then led to discovering that the render pipeline wasn't working correctly, except in my PC, which made the release unplayable anyway. And by that time I

had fallen 2 days behind the schedule in a 7 days sprint.

This all would have been fine if it wasn't because the whole "doing everything by yourself in a month" idea blew up in my face too. Essentially, I wasn't only behind schedule, but it was clear that the project wouldn't receive the

level of quality I would have liked. In a sense, we felt into the overly-ambitious pitfall more inexperienced developers tend to fall to because, despite having worked many times in projects where everything was being done from

scratch, and I was aware of the time it took, I had never done all the parts by myself. What went wrong here was a misdjudgment of implementation time on a series of concepts that were already deliberately

narrowed down to not be an excessive burden on the development process.

All in all, the end of the second sprint left the project in need for polish, and of some other more core parts like the level design, without empiric feedback to orientate the third sprint. Nonetheless, I leave links to the documentation

that was prepared to conduct the playtestings, even if they never happened at this stage, and thus they remain empty.

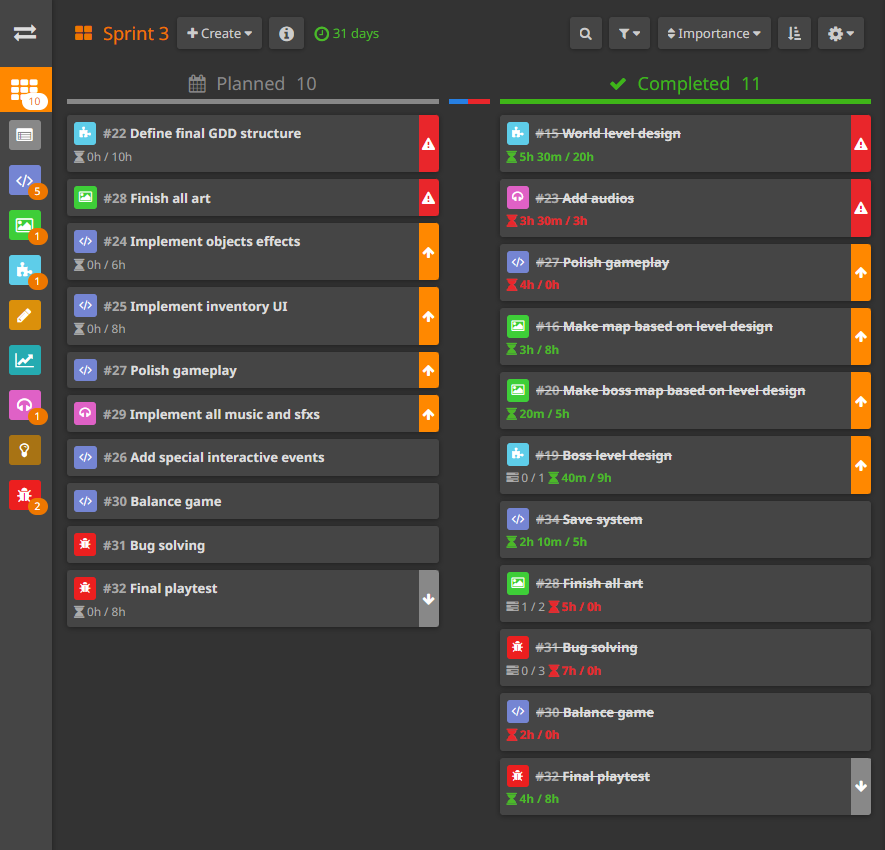

Third iteration

The final sprint was the shortest, by necessity, and it is very painfully clear. To give an idea of what this was like, all of the demo's audios were recorded and added to the game in a single afternoon; almost all of the levels,

seven out of the eight that comprise the demo, where conceived, made and implemented in three days, along an improvised pipeline that had to be added to improve the pacing. The rest of the time was spent solving bugs, testing by ourselves

the feel of the game, re-adjusting it, and then solving the bugs that appeared from said tweaks.

While that resulted in a rather stable final build, it was somewhat pointless to make an entire system to showcase design proficiency if the design, more specifically the level design, is set aside in favor of coding. Not to say that

it didn't have any thought put behind it, but it clearly doesn't have as much as it would have been desirable; regardless, I will leave the documentation publicly available:

Playtest feedback

After conducting all sessions with every available playters on the final iteration of the game, the given feedback was put into order. First we will expose various metrics we were keeping track of, their rate of success, and any additional comments if pertinent:

- Clear understanding of level transitions: 100%

- Clear understanding of the crafting system: 80%

- Clear understanding of the stress system: 60%

- Smoothness of player - boss interaction: 40%; the basic premise was clear, but most of the details were completely missed

- Clear understanding of the save system: 20%

- Adherence to the game loop: 60%; the cases outside this sixty percent are of players who just run forwards without caring for traps. That is a playstyle the game was designed to allow, but we were interested in seeing how easily would players be swayed to follow the resource-farming playstyle

- Clear understanding of level gimmicks: 60%

- Boss behavior feedback:

- Add a transition state with unique audio cue to indicate switch from walk to chase (feedback + clarifies use of mouse trap)

- Give bossses a sprite that screams "I cannot be killed by a rando with a stick"

- Initial cinematic, needed to:

- Clarify types of traps and their utility

- Clarify boss behavior

- Define stamina - stress relation

- Add a narrative motivational element

- Clarify that they will need to return there, hence the need to save resources to come back

(it's almost like the game was designed to work by relying on this cinematic being implemented from the start :') - Animation feedback:

- Attack animation should reach further, and collider should be better adjusted

- Running collider should be thinner to facilitate movement

- More exaggerated animation for sound enemy, to make it clear they cause a screen shake

- Add a unique "set trap" animation to make it clear why the player stops moving

- Movement direction animations should update to the last accepted directional input (not just the last one read)

- Add a particle to player "run" state to indicate a sound event being triggered

- Add audio cue to mark that stress has begun building due to low stamina; just camera shake doesn't work being visual cognition is focused on movement

- Change wall collision from stopping the player to friction that drags them down

- Reduce "set trap" animation to 0.5s

- Change trap names to describe their effect, not their diegetic origin

Not so rare footage of the player getting stopped by colliding with the wall

Finally, this a list of other minor non-obvious corrections that would havt to be implemented:

- Change the generic "place trap" sound for distinctive ones per each type

- Change the disposition of the lobby entrances to condition players to enter the levels first (80% of the testers entered the boss room first)

- Put the exit of Level 1 inside the right wall, to avoid stress-building pushback cycle when starting level from it and going up to kill the mouse enemy

- Inputs should be disabled when changing maps (preferably with a transition that showed a title for the current level), to avoid both missalignments that ruin level design, and room transition confusion

- Level 2 boss should start further from the trap, so the player has time to see the trap in action

- Set a specific maximum amount of tiles for the light trap to stop the boss

- Devote more time on Level 4 to reinforce sound events and how they affect boss behavior

- Have different transitions for changing level and when dying, not just a generic fade to black

- Add a blinding effect to light enemies' attack, to tie them to the effect of the trap (not as intense, though)

- Indicate resource availability within the HUD

- Return player to main menu instead of closing the game when the end is reached (wtf was I thinking, to be fair)

- Use mouse to define where to set traps

Project closure

In the end, I can't say I am satisfied with the results of the game. While it is not my first project from scratch, nor any of what I had to do was new to me, its is the first time I had to handle

everything at the same time. Most of the bigger projects I've worked in were done in three months, so in retrospective, it is relatively satisfying to have an actual playable demo in a third of that time, but my vision of the game involved a

narrative side that has been totally erased from the final release, as well as other minor mechanics that didn't make the cut. And of course, I do not ignore that the game looks and sounds rather... poorly. What may hurt the most,

though, is how poorly its levels are designed; while I still think that the base triangularity of stress and trap crafting by using shared resources works, having only three days to create the contexts that should make those mechanics

shine was not enough time, and it shows. From the fourteen levels that were prepared, only ten could be implemented, not to say tested and balanced. In the end, that is a bit the summary of the project: a half-cooked but functional demo. I won't invest more time in it, because the purpose of the series is to specifically show

what I can do in one month of work, but looking back, I am aware it could have been done better.

If I were, however, to fix the current issues, aside from getting someone who can do the art, I would iterate the level design. First of all, I would expand the amount of interactions we explore, increasing the amount of content. Additionally,

it would be proper to work on the reverse level traversal. In case you haven't read the GDDs, since the end of the game is at the start, all completed levels will have to be done backwards, but since we can't have them be empty, dead space,

the levels are designed in such a way that they are played differently (and interestingly) both when the player goes forward and backwards. While there are some levels that do work, many others don't offer the difficulty necessary for that point in the game, specially because the boss is too far from the

player to be a threat until the end of the level.

It would also be benefitial to apply a local routing framework for multi-path levels, like the Level 5 and the Final level, which were made applying generic (albeit valid) notions of challenge, lacking cohesion and adequacy to the type of design they demanded. On that topic, the

final level should be much longer, to build a more satisfying conclusion, and have much more fluctuations in pacing, as right now it is a straight race towards the exit. Finally, I would actually have resource distribution adjusted to

the calculations made in the corresponding document. Conducting proper playtesting during this re-design process would, obviously, be part of the key factors that would help in making successful iterations.

All those points being made are relatively simple to make, probably wouldn't take more than a week, and require no changes to the game's features. As it was stressed, what impeded those modifications to make it to the final version

wasn't their complexity, but my lack of time within the self-stipulated development period. Of course, there are things that would require bigger changes, like a narrative layer, but since this section was to hypothesize how to approach

the current content's flaws, it won't be discuss any further.

Conclusions

The other side of the many mistakes is the many learnings that come with it. The big obvious one is to not try to do what I am not prepared to do, mainly the artistic parts, but also what I can do, but am not looking to invest

time in, like the code, which could have been borrowed from already existing game engines I am proficient with. This will be directly reflected in the next entry in the series. Another key learning is on how to organize playtesting

releases: if my approach until now was to simply work until the playtesting day comes, and ensure the release works, it should adapt to having a build ready for a prior testing session that ensures the real playtesting will

proceed without problems.

Release link

Download link. A horrible idea, really